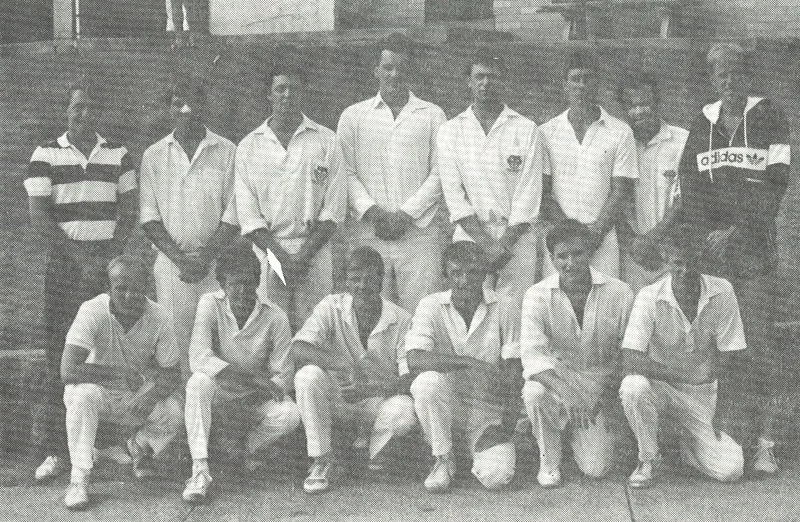

If you flick through the Club’s Annual Report for the 1986-87 season, you might notice a grainy, black and white photograph of the Poidevin-Gray Shield team. At first glance, the team it portrays looks like a typical University Under-21 side of the time, liberally stocked with the products of Sydney private schools, playing some decent cricket while they study, together with a sprinkling of promising country cricketers. If you know a little bit about the University cricket of this period, you can look at the photo and guess what will happen to these young men. Most will finish playing cricket not long after they graduate. They’ll become lawyers or accountants, vets or engineers, and on summer afternoons they might glance out of their office windows and remember, fondly, the days when they had nothing more urgent to do than chase a ball around a field. Some of the country boys will go back to the land. It’s a familiar tale.

But look more closely and two things stand out. First, this was a distinctly successful team, unbeaten until it lost to Mosman in a closely-fought final. University teams today reach finals almost out of habit, so it’s worth recalling that in 1987 University had never won the Poidevin-Gray Shield and had reached the final only once, in 1959-60 (when, by coincidence, Mosman also won).

The other conspicuous feature of the team photograph is the towering figure standing in the centre of the back row. It’s the team’s opening bowler, Russell Merrick Oldham, a Science student from Wollongong – at 195 centimetres tall, and wide across the shoulders, an imposing physical presence. This wasn’t a team that expended a great deal of intellectual energy on nicknames. The manager, St John Frawley, was “Sinj”; Gary Lennon was “Gaz”. In this environment, it was no surprise that Oldham soon became “Big R”.

Oldham had joined the club at the start of the season, unheralded and unannounced. He was raw and unconventional, a large man in ill-fitting gear who bowled inswingers from an uncommonly short approach. Without being very fast, he hit the bat hard. His cricket trousers were bright white and flared at the ends, and soon became known as his “disco cricket slacks”. He was not yet twenty, but his dark hair already had flecks of premature grey. He didn’t fit neatly into any mould, and the club’s selectors had no real idea what to do with him. So they sent him out to Parramatta Hospital, to play City & Suburban cricket with the Veterans – where he opened the bowling wearing sandshoes. The following week he was promoted to Sixth Grade, where he scored 29 not out and took 3-21, earning an immediate promotion. He played only one game in Fifths, opening the batting and scoring 35, then just one in Fourths before he was lifted into Third Grade.

St John Frawley was the manager of the Poidevin-Gray team that season. He remembers that “Skull (Kerry O’Keeffe, the Poidevin-Gray coach) and I ran a training session on the old nets near St John’s, and this absolute hulk wandered down in bare feet and started bowling. We watched a couple of balls, and Skull said, “My God!” and took Russell off to buy him a pair of shoes.”

In the first half of the season, Big R played his best cricket in the Poidevin-Gray team, bowling long, miserly spells and regularly collecting wickets. He bowled almost unchanged through the 60-over innings against Parramatta, taking 5-84, and wrecked Campbelltown with 5-39. In the final, against Mosman, he bowled 17 overs for only 40 runs, effectively containing future England batsman Jason Gallian and Somerset county professional Nick Pringle. Kerry O’Keeffe, praised the “heart, stamina and raw talent” of “our fast bowling lynchpin of the six metre run-up”. In the Poidevin-Gray season, Oldham was scarcely needed to bat, and didn’t score a single run; but when he promoted to open the batting in Third Grade, late in the season, he responded by thumping two successive centuries, against North Sydney and Mosman.

Plainly, the Club had stumbled across an exceptional talent. He was an unusual character, too – heart-warmingly loyal to his friends, but with a disconcerting readiness to threaten violence to anyone who upset them. He was gregarious and popular, and loved belonging to a team, but was also a little dark. “He was quiet, humble and thoughtful, and very warm”, recalls St John Frawley. “And he was a mighty talent. But there was an air of mystery about him. He wasn’t one of those people who’d sit you down and tell you his life story, and no-one was really sure where he came from. He was supposed to be on a BHP scholarship, which was how he could afford to live at St John’s College, but no-one knew for certain. Did he have a kid, or didn’t he? Why did he turn up without shoes? After the PG final, the team went out to King’s Cross, and then we got the first hint that there was this wild side to him.”

Anyway, no-one underestimated him in his second season. He was graded in Seconds, and responded by bowling tightly and efficiently, and whacking a match-winning, unbeaten 60 against Parramatta. On Sunday 15 November 1987, he played in the First Grade Limited Overs side against Northern District at Waitara (in a match which has, retrospectively, been recognized as a full First Grade game). He bowled his ten overs tidily, conceding only 37 runs and capturing the handy wicket of future University captain Brad Patterson. He also batted for a time with Test batsman John Dyson, before he was bowled by the NSW fast-medium bowler Neil Maxwell. In this very distinguished company, he didn’t look out of place.

This might have been the start of a bright First Grade career – instead, it was virtually his last cricket match. When the University term ended, he dropped out of the game, insisting that he needed to work. It was said, and might even have been true, that he needed to support his infant daughter from a failed relationship back in Wollongong. Then he dropped out of University as well. He began to work as a doorman for nightclubs in King’s Cross, and found that the job was perfectly suited to his personality – as the occasion required, he could be genially welcoming, or forcefully dismissive. His friendly nature and capacity for violence were accommodated in equal measure.

In the murky world of King’s Cross, Oldham stood out. There were King’s Cross operators who were as strong as he was, and others who were just as intelligent, but few (if any) who could supply his particular combination of brain and muscle. He soon came to the attention of Philip Player, a nightclub owner and self-styled gangster (who was later jailed for conspiracy to murder). Player offered Oldham work, and was soon involving him in the management of the Bonnie and Clyde club in Newtown. He presented Oldham with a gun, his first, and introduced him to the Sydney underworld’s drug distribution networks – which was where he spent most of the next ten years.

On 5 April 1998, Oldham and at least five other men drove to Bankstown to meet with Orhan Yildirim and Mehmet Unsal, who were accused of reneging on some illegal deal. The details of what followed are unpleasant, and the encounter ended with Yildirim and Unsal being shot at close range. The Police prosecutor described it as a “gangland execution”. There was never any evidence that Oldham himself inflicted any of the injuries, but there was no doubt that he was present at the scene of the crime. Charged with murder, he was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to six years in prison.

He was, it turned out, a model prisoner, active in supporting children’s charities, and he was released from Goulburn early, in November 2004. Before his prison term, he had been loosely associated with the Outlaw bikie gang; afterwards, he joined the Bandidos. There’s a story that Rodney Monk of the Bandidos sent a limousine to Goulburn to collect Oldham when he was released. Some accounts insist that Oldham then became a Sergeant-at-Arms in the gang, while others say that he was merely a probationary member. Paperwork not being very high on the list of Bandido priorities, the truth is elusive. Actually, there are very few uncontroversial facts about Big R’s time with the Bandidos: he had entered a world in which verifiable truths are swamped by rumours, allegations and innuendo. It’s said that he was involved in manufacturing ice and amphetamines, and that he acquired a taste for his own handiwork, but it’s impossible to know how true this was – the Bandidos’ core business at the time was cocaine. What did complicate his life significantly was that he began a relationship with the woman who was assigned as his parole officer, which was considered an infraction of the Bandidos’ rules (and how many other organisations, incidentally, need rules about parole officers?). Possibly this was why Oldham fell out with Monk, who held a position high in the gang’s hierarchy, although some stories say that Monk wanted to expel Oldham for other acts of indiscipline and still others claim that Oldham had backed one of Monk’s rivals for a leadership role in the gang. All we know for sure is that on 20 April 2006, Oldham rode to Bar Reggio in East Sydney to speak with Monk. The two men became involved in an argument, and left the restaurant to continue their conversation in a laneway, while Monk’s bodyguard remained, inexplicably, inside. Three shots were fired, and Monk died almost instantly.

For three weeks, Oldham went missing, eluding an intensive Police search. Then on 11 May, just after sunset, he walked into the sea at Balmoral Beach, put his gun to his head, and fired a single shot. In the days that followed, many newspaper reports insisted that this was the act of a man whose mind was addled by ice addiction. It’s more likely that he was thinking with perfect clarity. He knew that he would be discovered soon enough, either by the Bandidos, who would deal with him brutally, or by the Police – in which case, he would go back to prison, where the Bandidos would deal with him brutally. There was no way out.

The unhappy ending to this story seems to cry out for a moral of some sort, and you can make it mean almost anything you like. Wasted talent is a tragedy. Crime doesn’t pay. Drugs harm people. All true enough. But if we need to draw a lesson from all of this, maybe it’s a touch more complicated than that – because what the story really shows is the danger that lies in making lazy assumptions about people. Oldham was a gangster implicated in terrible violence yet still, on other occasions, was a warm, thoughtful and generous person; his character can’t be reduced to a single dimension. You can’t assume that once you know his crimes, you know the man. Any more than you can look at a photograph of a group of young cricketers and assume that you know how the story ends up.